More Evidence that Gender Affirming Care is Good Medicine

A new study from Boston Children’s Hospital adds to the body of research supporting the use of puberty blockers for trans youth in early puberty.

by Evan Urquhart

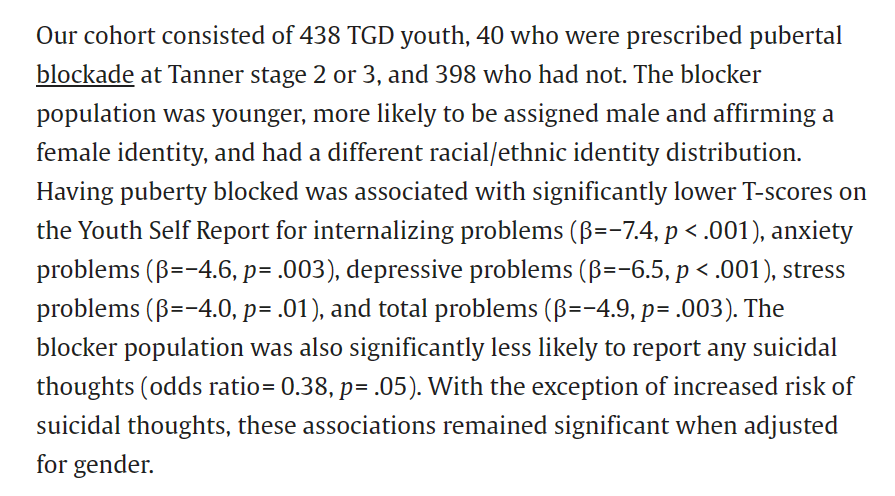

A study out of Boston Children’s Hospital published last week in the Journal of Adolescent Health by McGregor et al. found that trans youth who received puberty blockers early had better mental health than youth who didn’t. This finding adds to the growing body of evidence on the efficacy of medical treatments for gender dysphoria in youth, which was already quite substantial. Children being evaluated for hormone therapy after having their puberty put on hold scored significantly lower on a range of mental health measures including anxiety and depression, among others. The group who received puberty blockers were also significantly less likely to report thoughts of suicide.

Researchers looked at the files of 438 transgender youth who had been evaluated to see if they were ready to start hormone therapy between the ages of 13 and 17. Of this group of patients, 40 had already received a blocker in early puberty before being assessed for hormone readiness. The clinic recommended blockers for youth in early puberty, so those who were assessed to start hormones and hadn’t received a blocker were already in late puberty. The clinic would not allow youth to be assessed for hormone therapy before they turned 13, and the study left out youth who received blockers in later puberty in order to focus on those who had their puberty paused early.

A large number of youth in the group that hadn’t received blockers were 16 or 17 when they were assessed for hormone therapy, while all of those who had received a blocker were between 13 and 15, so the authors re-analyzed the data with only the 13 to 15-year-olds. They again found that the group who received blockers had less anxiety and depression, but the differences in suicidal thoughts were no longer significant.

As you can see in the screenshot above, the group who received blockers were also more likely to be transfeminine. Specifically, 35 percent of the group who received blockers had a male gender identity, compared to 73 percent of the no blocker group.

Some critics of the affirming care model believe there are distinct types of gender dysphoria that show up at different ages, although researchers across the spectrum largely agree there is no evidence for this. The differences in age and birth-assigned sex for youth who did and did not receive blockers found here might play into this for people who are either unused to reading studies or intentionally seeking to distort results to fit their narrative. Therefore, it’s important to note that there are also differences between assigned male and female youth in the age of onset of puberty, and these differences are very likely to result in fewer female-assigned youth being in the group who received blockers in this sample.

For female-assigned youth, the normal age that puberty begins is is between 8 and 13, while male-assigned youth start puberty a little later, on average between 9 and 14. At Boston Children’s, the average age that youth received a puberty blocker was 12, and youth were not able to be assessed for hormone therapy until they turned 13. The average age of a first period for female-assigned youth is 12. If a young person first came to the clinic before they turned 13 but were in a later stage of puberty, they would only have been eligible for a puberty blocker, and not for hormone therapy. It’s impossible to know how common that scenario was based on this paper, but because puberty begins earlier for female-assigned youth it would be more likely for them to find themselves in that situation, and therefore more likely to have been in the group that was excluded from the analysis.

Of course, this was likely a small group among the 13 to 15s only. A much larger group, 223 of the youth assessed for hormones without having a puberty blocker, were assessed at 16 or 17. Of these older youth, 80 percent were assigned female. This follows a well-known trend of more female-assigned youth showing up at gender-clinics, despite the fact that when you ask youth directly about their gender identity directly the sex ratio is roughly equal. Since parents and doctors play a larger role in deciding whether a child will be seen at a clinic, social factors influencing adults are the most likely reason for this disparity.

Research into the best treatments for gender-dysphoria in youth continues to move forward, and the picture continues to support the use of puberty blockers and cross sex hormones. This most recent study supports the idea that catching gender dysphoria early, before puberty has advanced past Tanner 3, may be the most beneficial for young trans people.