When You Can’t Fight for Yourself, Fight for Your Community

Sometimes, when you can’t fight for yourself, you fight for the sake of those around you. Naseem Jamnia brings their perspective on what keeps them going.

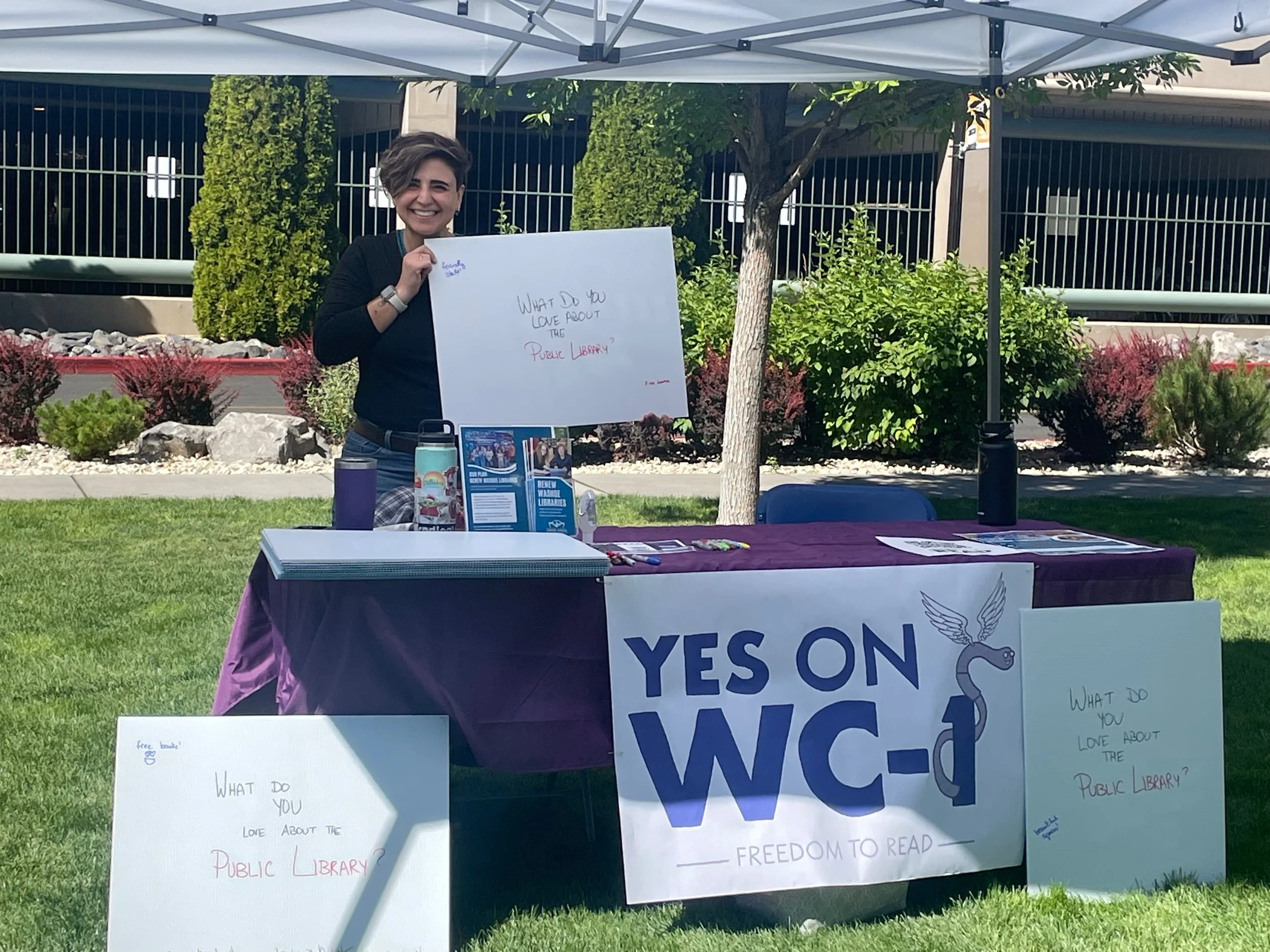

Photo by Tara de Queiroz

by Naseem Jamnia

It’s hard to be trans and motivated to do much right now. Waking up often feels like a victory. Walking the dogs means I made it out of the house. When people ask me how I’m doing, I say, “I’m alive” or “I’m here,” since that’s what I can muster. After all, why bother getting out of bed when the world outside my window has declared, in no uncertain terms, that it hates people like me?

Let me tell you my story of change and how, to keep going, I’m focusing on community.

The day after the 2016 US election, I sat on my couch in my Philadelphia apartment and sobbed for two hours. Although I’d been using the term nonbinary to describe my gender for about a year, it was that summer that I started using they/them pronouns and began to think of myself as trans. I’d come to Philly to start a PhD program in neuroscience, but that morning I made the decision I’d been dancing around for months: to quit science and write full time, hoping that was a more direct way to affect change.

Fast forward to the day after the 2024 US election: I found myself in a completely different emotional state. With the deadline for copy edits on my next book approaching, I found myself unable to work not because of fear or grief, but because I was numb. I was grateful that my Muslim parents and classically autistic brother had recently moved from their Wisconsin suburb, in the district of former Republican congressman Paul Ryan, to the middle of Massachusetts. At least in their new location, signs supporting both parties were in equal number. Still, this relief was tempered by the knowledge that our country’s slow descent into fascism was about to plummet head first.

Truthfully, I was expecting the results. It’s hard to be a queer, trans, neurodivergent person of color and child of brown immigrants and hold onto hope that a Black South Asian woman espousing centrist viewpoints would have a chance against her opponent. It’s hard to take seriously those who say these results don’t reflect our “American values” when the US is built on a capitalist, colonial, genocidal enterprise at home and abroad.

What hit me hardest, though, was the knowledge that my immediate community was about to be devastated. I’m an organizer with Freedom to Read Nevada, and for the past few months, we’ve been working on passing a local ballot measure to renew a tax allocation that has kept our county public library system funded for the past 30 years. Nevada, this famous libertarian state, has had its share of detractors who come to library board of trustee meetings and county commissioner meetings to make sure their Christian nationalist agendas are heard; but in the Reno area, where I reside, there have been many vocal supporters who, regardless of political affiliation, believe in “live and let live.”

The measure failed. The Washoe County Public Libraries are about to lose a quarter of their budget, about $4.5 million a year.

That morning after the election, I stared at the results, knowing that even as ballots were still being counted, we’d lost. We’d worked our butts off on the campaign, but we were a handful of concerned residents who happened to have a political consultant working with us pro-bono—with that exception, none of us were in the political realm. How could such a small group of everyday folk affect political change?

Ultimately, everything is political, including access to our public libraries. As one of the last third spaces, libraries provide education and resources to anyone regardless of identity, beliefs, or class. The knowledge safeguarded in libraries and the expertise in library staff is one key way to fight misinformation in the digital age. Library programming is vital for child literacy. Librarians help people not just find books, but look for housing, jobs, and legal advice. They’re even key places to monitor and improve public health.

In other words, public libraries are a cornerstone of any democracy. As someone who grew up in the large library system in Chicago—volunteering for six years as a kid; coming every weekend with my brown, neurodivergent family and feeling like we belonged there—they’ve long been a cornerstone of my life. And I’m not the only one who feels this way.

Since the election, most days I wake up not wanting to do anything but sit on the couch with my pets and crochet or play video games. But then I remember every librarian who has thanked me and our Freedom to Read Nevada team for fighting on their behalf. I remember how, at multiple board of trustees meetings, conservatives screamed at the library director and called him a sexual deviant, and how impassive his face remained as he took the abuse in stride—because that’s somehow become part of his job. I remember how the head of library programs told me she was getting voicemail death threats, and she wasn’t the only one.

Nowadays, I don’t feel like doing much for myself. But I’ll be damned if I stop fighting for others, and that keeps me going.

Naseem Jamnia (they/them) is the Crawford, Locus, Astounding, and World Fantasy award-nominated author of adult fantasy novella The Bruising of Qilwa, which introduces their queernormative, Persian-inspired world. Their debut middle grade horror, The Glade, comes out May 2025 from Aladdin. Find out more and join their newsletter at NaseemWrites.com or on Instagram @Jamsternazzy.